Lagos and the rise and rise of AfroBeats

By Olatunji Oke

By Olatunji Oke

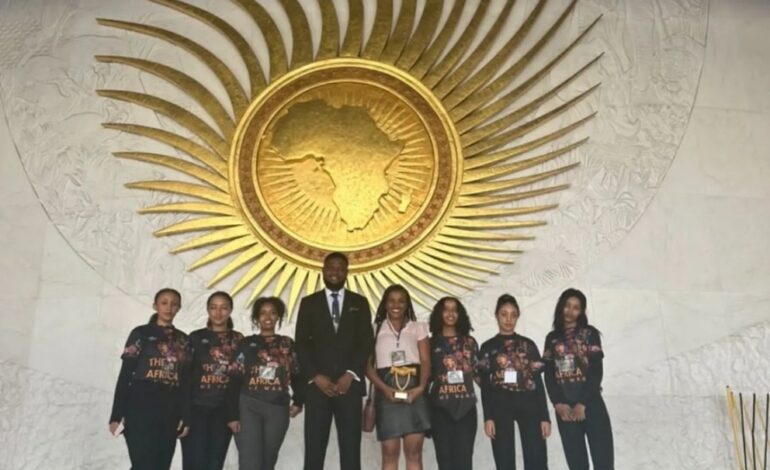

When the artiste Davido had a concert to mark the release of his most recent album in April 2023, it was advertised as his “homecoming concert.” It was the same when Burna Boy had his in January and even though it was ultimately botched, Wizkid’s 2022 concert was designed to be his homecoming show. As a matter of fact, his Grammy-winning album was titled “Made In Lagos.” All three superstars are widely as being the biggest acts on the continent and all three speak freely of their respective places of origin (Ede in Osun State, Port Harcourt in Rivers State and Ijebu Ode in Ogun State), yet all three think of Lagos as their home.

But it’s not only Davido or Burna Boy or Wizkid: as Afrobeats has continued to enjoy a supersonic rise across the world that has seen its stars sell out stadiums, win the biggest prizes and become a generational identity, everything finds its way to Lagos. It doesn’t matter if your career is just starting or you’re at the pinnacle of your art, Lagos is where Afrobeats began and is intrinsically responsible for the continuous success of Afrobeats in the world.

In the beginning, there was Lagos The history of Afrobeats is only just being written, which is why this writer has worked quite extensively on curating and documenting its story. In 2020, my first book History Made: The Most Important Nigerian Songs Since 1999 was released and it tells the history of the genre through twenty-one songs that have defined the era through its various iterations. I was also part of the two documentaries that tell the history of Afrobeats: the Backstory by Ayo Shonaiya and Journey to the Beats by Obi Asika. What historians and culture custodians agree on is that the genre Afrobeats started around 1999 when the first wave of commercially successful musicians and labels sprang up and started to make waves (no pun intended).

In 1997, Kenny Ogungbe and Dayo Adeneye who were broadcasters on Raypower FM formed a record label to distribute the deluge of music they were receiving on the newly founded independent radio station. Not that they intended to go into the music business. However, as radio personalities on a station that catered to the youth segment of society, upcoming acts almost instinctively gravitated to them.

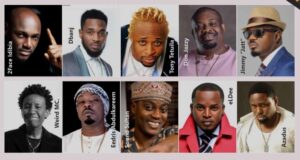

Their first signed artistes were the group Remedies comprising Eedris Abdulkareem and Eddy Montana. The two men were unknown to each other until the day they met at Raypower FM. Ogungbe threw them together to create a song on the fly and what they did was the single Shakomo. It was well done that the broadcaster played it live on air the same day. The group Remedies was born and even though it wasn’t formally registered until months later, the record label Kennis Music was born as well. By the time the group released its follow-up singles Judile in 1998, Sade in 1999 and their album, Peace Nigeria in the same year, it was clear that a new dawn was breaking. A third member Tony Tetuila would join for a short while during this time but he soon broke off and pursued a solo career.

Around this time too, a couple of childhood friends from Markudi who followed one another to the institute of Management Technology, Enugu had found their way to Lagos. Augustine “Blackface” Ahmedu and Innocent “2face” Idibia left IMT to chase their dreams in Lagos. Surely, Enugu was a hotspot in the eastern part of Nigeria and the city had at least five institutions of higher learning, but they knew Lagos held the key if they wanted to make anything of their talent. Platashun Boiz as they could come to be known, moved to Blackface’s uncle’s apartment in Festac Town and discovered that they had arrived at an artistic Eldorado.

It was at Festac that they met Chibuzor “Faze” Orji the third member of their group who was born right there in Festac. Built in 1977 for the Festival of Arts and Culture, it was as if Festac Town stayed true to the tenets of creative expression that birthed it. There were talented youngsters on every corner, from Sound Sultan and his brother Baba Dee, to Azadus and several others. Plantashun Boiz honed their skills in Lagos performing at small shows around town and as backup singers for Weird MC. They met Nelson Brown who had cut his teeth in the 1980s as a producer and got signed to his record label Dove Records. Plantashun Boiz’s journey to nationwide fame and acclaim took off when their single Don’t U Know came out in 1999.

But the music talent permeating the city of Lagos wasn’t restricted to Festac: it was the same at the University of Lagos where Lanre “eLDee” Dabiri and his own childhood friend Kunle “KB” Bello had teamed up with Iwaya-born rapper Mfon “Freestyle” Essien to form the group Trybesmen. OJB Jezreel (real name Babatunde Okungbowa) was older than this crop and had started writing, producing and making music in the mid-1980s. He held sway in Surulere which was yet another hub for artistically inclined individuals. What this meant was that 1999 was pivotal for Nigerian urban contemporary music.

Between the return to democracy that encouraged new businesses to boost the country’s economy, the growth of the media landscape that saw more independent radio and televisions follow Dokpesi’s Raypower/AIT as well as an emerging youth culture that saw young people do things rather than being on the street protesting the annulment of the 1993 elections and the following Abacha junta; Afrobeats was being birthed even the name hadn’t been created yet. The name Afrobeats wouldn’t be coined until over a decade later.

Yet to properly chart the course of Afrobeats, one must go even further than 1999. Obi Asika, creative entrepreneur and founder of Storm Records, holds the credit for the first record label dedicated to modern music for and by young people. His foray into the music business started as a young student DJ in London and on one of his visits to Lagos in 1986, he struck up a friendship with a young Lagos DJ by the name of Jimmy “Jatt” Amu who grew up in Obalende and had been earning a reputation as the go-to-guy for “young people music.” Obi Asika recalls being pleasantly surprised that Jimmy Jatt’s music collection was similar to his, given that London was closer to the unfolding hip-hop scene than Lagos of the mid-80s.

“There wasn’t really anything for young people at the time. People were doing reggae, pop… you had Majek Fashek, Ras Kimono but if you’re 17, 18; that wasn’t hot sauce,” he says on the podcast IMG.

The need for the so-called young people’s music led to him, Jimmy Jatt and a few other associates creating Enter The Dragon, a series of club parties held at the penthouse of Western House on Broad Street. Having experienced this success and proof that young people wanted a different style of music, he had the take-off point for Storm Records. What’s more, the artistes brought on were Junior & Pretty, an Ajegunle-raised duo who performed hip-hop in pidgin English and spoke about topics that the audience immediately resonated with: girls, church, NITEL, danfo and all. It was the first time would be done and even though the label took a long hiatus (ten whole years), the seed had been born: Nigerians had another choice of music to listen to that wasn’t indigenous music or foreign ones.

We could create our own sound.

By the time Asika returned around the year 2000, the seed had germinated into a huge tree of various stars and businesses. Everywhere you turned, there were talented artistes thriving and growing their fanbases.

There were concerts and magazines, neighbourhood gigs and campus parties, and what was once a dream was now a literal, physical reality. What a time to be alive!

Toast of the world

Today, when fans from all over the world fall in love with Afrobeats, it’s a testament to the years that have preceded these recent ones. In the documentary Afrobeats: The Backstory, Korede Okungbowa, widow of the late producer OJB who passed away in 2016 tells the story of a young Wizkid. You see, Wizkid had been practically raised in OJB’s studio and had been around the biggest stars to come out of Nigeria as they all invariably came to OJB for one melody or the other. On this day, Ms Korede recalls how Wizkid’s mother trusted her and her producer husband to take good care of her “baby” and how he would follow them to events around the city. On one occasion, there weren’t enough seats in the arena and she had to carry him on her lap so he could enjoy the show. Six years later, Wizkid had released his first album Superstar to instant success. That is the story of Afrobeats if one looks at it from the lens of the last ten years.

Perhaps it’s best to look at it in terms of eras and time bands. For example, while the first set of commercially successful artistes were Remedies, Plantashun Boiz and Trybesmen, the next era was when 2face broke out of the Plantashun Boiz leading up to the arrival of Dbanj and Don Jazzy around 2004. They were UK-based artistes who were seeing what was happening back home and realizing that they had almost a zero chance of making it on that level there, headed to Lagos to make it happen. Similarly, this was the height of the P-Square reign who even though had been making music in Jos and winning local singing competitions, they had to move to Lagos to have a fighting chance. Once they got that chance, P-Square became one of the most iconic acts to come out of Nigeria, selling out arenas all over Africa.

This era coincided with the rise in the participation of corporate sponsorships in Nigerian pop music. To draw an illustration of this boom, take the fact that eLDee of Trybesmen had to design a business model with music pirates to have his music distributed in such a way that they earned a return from it, and compare that to how D’banj got ten million naira in an endorsement deal for an energy drink brand. Those two moments are only five years apart. It was a sign of things to come, for they themselves and the industry at large. It didn’t matter that their once penetrable bond eventually collapsed and Mohits broke down; it was proof that it didn’t matter if they were based in London or drafted to work with Kanye West in New York, if they wanted to be successful, they had to make their way to Lagos, Nigeria and build from there.

The next era began circa 2010/2011 and has snowballed into a juggernaut incomparable to any force the African continent and the world have ever seen Wizkid, Davido and Burna Boy came on board around this time, as did Yemi Alade, Tiwa Savage and a host of others. Music had become a serious business with huge financial investments. Concerts had evolved from the days of Lekki Sunsplash in the late 1980s to multi-million naira stage sets at Eko Hotel. These days, we have exported that Naija Factor to the rest of the world where our artistes can comfortably stand toe to toe with anybody in the world. On the night that Burna Boy had a concert in London where sixty thousand people were in attendance, Beyonce had hers only five miles away in the same city with her forty thousand fans. That’s how far we’ve come.

Since then, the music has not abated. It hasn’t stopped. This current wave is directly linked to the success of the biggest names being at the forefront of the movement as the world tunes in. But before them, there was a solid ten-year period of commercial and critical success. Before that, there were twenty years of building models and feeling our way through. Where the music is right now, is a result of many things:

legacy, grit, perseverance, investment and continued investment – and the undefeatable Nigerian spirit. It is also a continuous amalgam of sounds: while the five-beat pattern that Fela used is at the core of Afrobeats, it takes from hip hop and fuji and highlife and juju (in recent years, amapiano has joined in). It defines a people, a culture. It’s not immodest to say that Afrobeats could only have been created by Nigeria and when we peel back just a layer, Lagos is where it happens.

Much Ado About A Letter

The name itself had been a knotty issue only until recently. The inclusion of the ‘S’ seemed like a corruption of the music Fela Anikulapo did, which is the globally acknowledged Afrobeats. The emergence of this new Afrobeats to describe Nigeria’s contemporary popular music came from outside of the culture: it was coined by UK-based media personalities who used it to refer to the various music coming from the motherland. In time, music of Nigerian origin became the most dominant sound coming from Africa and having direct descendency from Fela, Afrobeats is Nigerian.

Prior to then, it didn’t have a specific name it went by.

The title it took on was “Naija pop” or “Naija hip hop” and the reason wasn’t far-fetched: the earliest practitioners who were raised on indigenous music like highlife, Afrobeat, fuji and juju were also influenced by hip-hop and pop music. For many purists and older Nigerians, the term was an affront;

especially when they consider that Afrobeats with the S has little in common with the militant, conscious music Fela performed. We say to them, coolu coolu temper! Most of today’s acts hold Fela in high esteem as they should, despite the fact that a great number of them were not alive when Fela was active. If anything, Afrobeats artistes revere the artistry of Fela and cherish his genius compositions.

Speaking of Fela, the late icon himself had to come to Lagos to find himself. In Fela: This Bitch of A Life, his biography written by Carlos Moore, he recounts how as at the age of sixteen, he would sneak to Lagos with his school friends all the way from Abeokuta. “We’d take my mother’s car, for example. We loved the night, man. We’d go to Lagos, night clubbing. Oh wow, I was finally having a taste of life, the real life!” It didn’t matter that his peregrinations would take him to London and Accra and Los Angeles, Lagos was his home. He sang about it in his 1973 record Eko Ile: “Ko ma si ibi ti mo le f’ori le/ Kosi o, a’fe Eko ile. Bi mo nba rajo lo London/ Ma tun pada si Eko ile/ Bi mo nba rajo si New York, Ma tun pada si Eko ile…” (There is no place where I can lay my head/ None, expect Lagos my home. When I travel to London/ I’ll always return to Lagos my home/ When I travel to New York, I’ll always return to Lagos my home). Fifty years later, it’s a truth that endures. Lagos is where it happens.

Lagos is home.